The In Crowd, Part 2

Before the China Law Blog posts, I had promised to flesh out the ingroup/outgroup picture I sketched in the first In Crowd post. In that post I questioned the standard descriptions of the U.S. as "individualist" and the Chinese as "collectivist," pointing toward the distinction between ingroup and outgroup as one possible way to clarify how individuals and groups relate to each other in the U.S. and China. I'll pick up by repeating the last two paragraphs of that post and continuing from there.

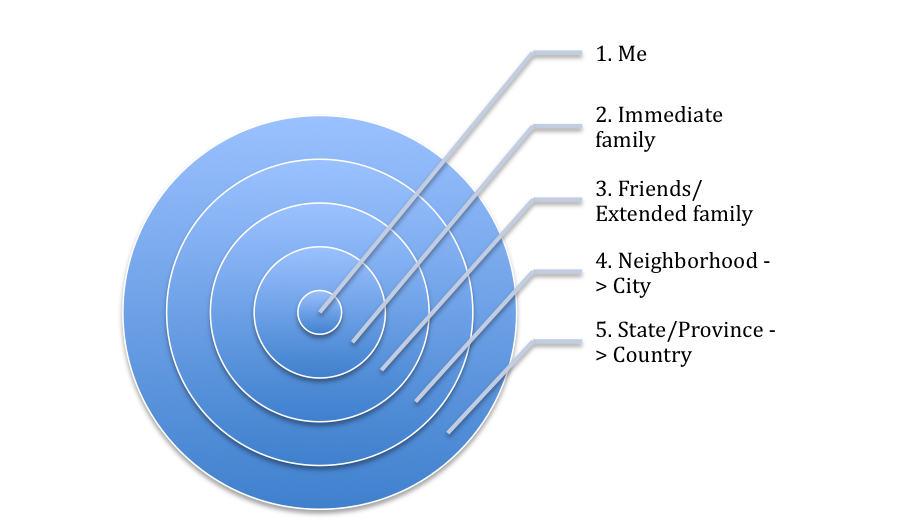

One of the key differences between Chinese and U.S. culture is where ingroup boundaries get drawn in society as a whole. The rule of thumb is that Chinese culture involves narrower group boundaries: ingroups are very small, perhaps consisting only of a person and her immediate family. Everyone else is an outgroup member, and is generally treated with a degree of suspicion.In the U.S., in contrast, people are more willing to consider a broader range of others as potential ingroupers — hence Americans’ famous (and, viewed from some perspectives, cloying, and even insincere) friendliness toward strangers.One way to represent this would be:

To massively oversimplify: ingroup boundaries in China don’t venture much past circle #2, while American ingroup boundaries might extend all the way out to #5.

It’s oversimplified in many ways. First, the People’s Republic of China as a whole is certainly an ingroup in the context of the world — hence patriotism. Same with the U.S. Second, ingroups can and do crosscut geography: religious, ethnic, and racial groups, for instance. There is just no simple way to accurately depict all the complexities of ingroups and outgroups.Caveats aside, there really is something to this. And if this is true, then we could make the case that Americans, with their more inclusive group sense, are the true communitarians, while the Chinese are the true individualists.

Lin Yutang, one of the most famous interpreters of China to the West, wrote of this in his most famous book, My Country and My People. He wrote it in 1935, before the full occupation of China by the Japanese, before the rest of World War II, before the Communist revolution and Mao Zedong and the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution and Deng Xiaoping and Tian’anmen and Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. He wrote the book in English, after having lived in the U.S. for several years. Nobody before or since has written with such clarity and wit about fundamental aspects of Chinese society.

He kicks off Chapter Six, “Social and Political Life,” like this:

The Chinese are a nation of individualists. They are family-minded, not social-minded, and the family mind is only a form of magnified selfishness. It is curious that the word “society” does not exist as an idea in Chinese thought.…

“Public spirit” is a new term, so is “civic consciousness,” and so is “social service.” There are no such commodities in China. To be sure, there are “social affairs,” such as weddings, funerals, and birthday celebrations and Buddhistic processions and annual festivals. But the things which make up English and American social life, viz. sport, politics and religion, are conspicuously absent.…They play games, to be sure, but these games are characteristic of Chinese individualism.…Teamwork is unknown. In Chinese card games, each man plays for himself. (Lin Yutang, My Country and My People, Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2000 [orig. 1935], p. 169.)

Of course this is one man’s opinion. All grain-of-salt warnings remain in force. At the same time, this was a particularly insightful person.

And he is not alone. Observers East and West, as well as a great many social scientists (chiefly psychologists, but also anthropologists and linguists), have provided further evidence for an enduring Chinese mindset roughly along the lines sketched out here by Lin, and echoed in my research.

So, if “the Chinese are a nation of individualists,” what are we to make of the famous distinction between U.S.-as-individualist and China-as-collectivist? Clearly the distinction does not work if it is interpreted too literally or too strictly. Instead, a more nuanced view of what constitutes “groups” in a society will allow us to keep what works about the distinction, without forcing us into inaccurate conclusions.